Our story begins in 1954 when the Egyptian government decided to build a dam across the river Nile, a project whose aims included better control of the river’s floods and the generation of the electricity that Egypt needed. Located in Upper Egypt at Aswan, the dam would create a huge reservoir behind it. This reservoir (Lake Nasser as it was later named) however would flood a huge section of the Nile valley. That was a problem because the valley was where human beings had been living for millennia and it contained uncounted known and as yet probably undiscovered remains of Nubian, Egyptian, Roman, and other civilisations. If nothing was done, all of this would be drowned and lost forever.

In 1959 Egypt asked UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, for help in rescuing the treasures of ancient Egypt. The response was a salvage operation that took twenty years to complete. At the time however, it’s unlikely that anyone could have foreseen that it would also lead to the UNESCO World Heritage programme as well.

The Aswan dam was crucial to Egypt’s economic development but the area marked for inundation was also the location of hundreds of ancient sites including the Abu Simbel temple complex (built by Ramses II in the 13th century BCE) and ancient Philae (renowned as “an outdoor museum of Egyptian architecture and art”).

Egypt’s appeal fortunately did not fall on deaf ears. For one thing, the region of ancient Nubia was something that the international community was very familiar with: it was where some of the earliest European explorers had ventured and it had been the subject of intensive archaeological investigation since the 19th century. Gearing up to preserve the Nubian archaeological heritage, UNESCO organised an international conference in 1959. Experts visiting the area marked for inundation recommended carrying out emergency salvage excavations and relocating structures above the anticipated high-waterline.

Concurrently with this, UNESCO also launched an international campaign to solicit donations to finance the rescue operation. Two years later, a UNESCO-led committee was set up to oversee the world’s first and biggest long-term international heritage-preservation effort at Abu Simbel. Fifty countries contributed financial support to a multidimensional project that brought together more than two thousand archaeologists, architects, conservator-restorers, engineers, and other professionals from France, Germany, Italy, and Sweden, as well as from Egypt.

To draw international public attention and to attract more funding for the project, Egypt also took the innovative step of organising a travelling exhibition of 34 objects from the tomb of Tutankhamun. Dubbed “Tutankhamun Treasures”, the exhibition was mounted in the United States, Canada, Japan, and France in 1961-1967. An expanded selection of material from the tomb appeared in a second exhibition, “The Treasures of Tutankhamun”, which opened at the British Museum in 1972 and which remained on tour until 1981 and also visited museums in the US, Russia, and Germany. The money generated by admissions to these appearances was used to finance the Abu Simbel project and other UNESCO campaigns. For example the 600 thousand pounds in profits from the show at the British Museum were used to relocate threatened ancient artefacts on the island of Philae. Thanks to UNESCO’s exhibitions, the Tutankhamun tomb treasures number among the world’s most-travelled artefacts.

Saving Abu Simbel

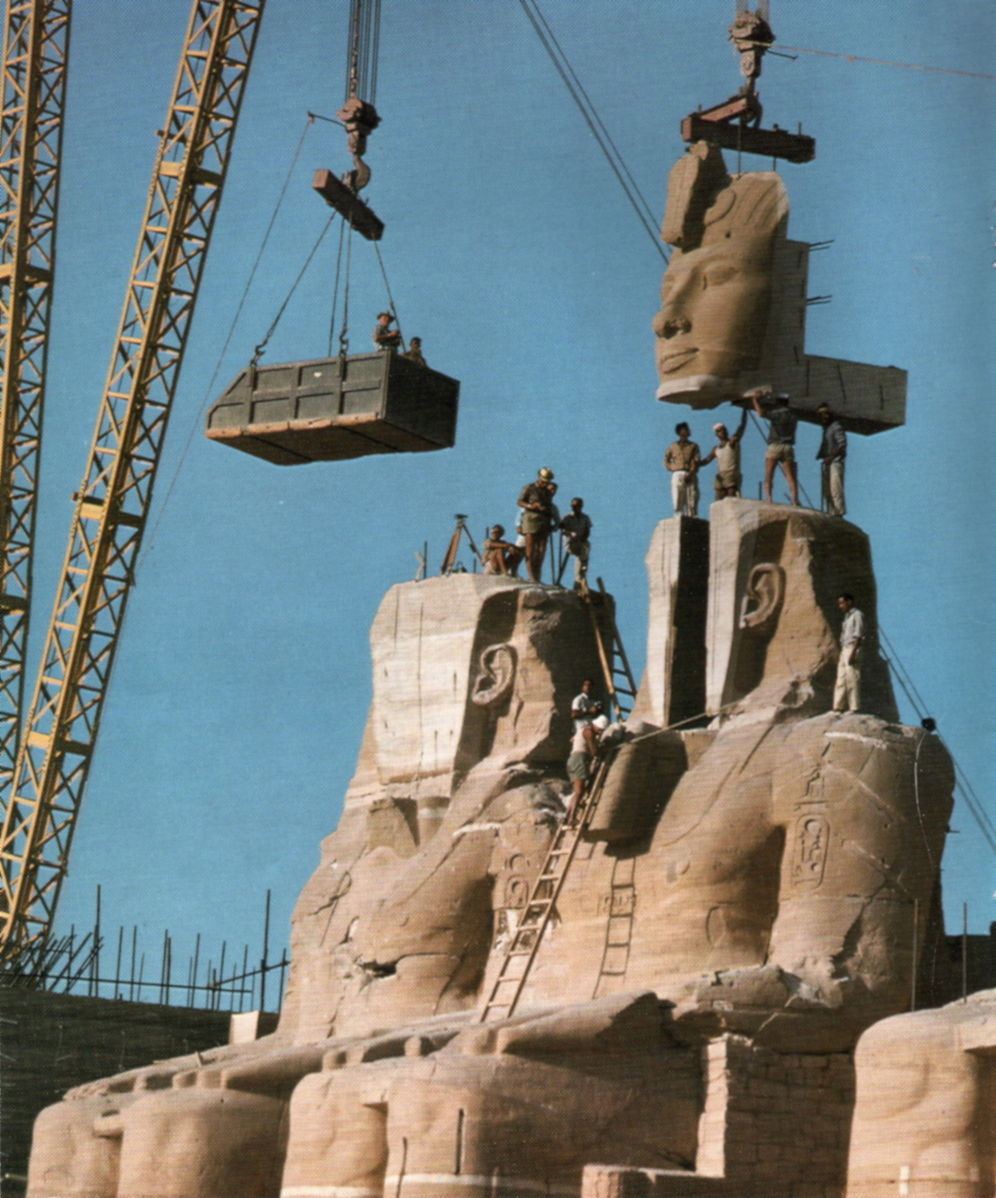

The first–and hardest–part of the project was relocating the twin temples at Abu Simbel. The problem was that the complex, a manmade marvel weighing a quarter of a million tons all told, had been carved directly into the face of a cliff. Relocating it would push the boundaries of technology available at the time. Ideas about how to cope with this enormously risky project flowed in from all over the world. One involved creating a gigantic “aquarium” around the temples with elevator-accessible underwater viewing chambers for visitors. This was rejected on the grounds that the monuments would suffer from long-term submersion. Another idea that attracted attention involved raising the temples gradually on hydraulic jacks until they were above the waterline. That too was rejected due both to its cost and to the risk of catastrophic damage in the event of jack failure. From among the many proposals that were advanced, it was decided to go with the one that was physically the most challenging: dismantle the temples by cutting them into massive blocks and reassemble them somewhere else.

Carving up 3,000 years of history

Work at Abu Simbel got underway in spring 1964. First of all, a cofferdam was erected around Abu Simbel in order to gain additional time in which to work on the temples while water was collecting in the Aswan dam’s reservoir. The salvage operation involved three stages: dismantling, transporting, and reassembling. Scaffoldings were erected at both temples to support their individual elements. The thorniest problem was separating the complex from the cliff because there was much more to the temples than just the facades that were visible from the outside: inside there were also chambers, hieroglyphic-inscribed walls, and sculptures, all of which would also have to be relocated intact. The decision was made to carve up a huge mountain’s 3,000 years of history into more than a thousand blocks, each weighing between seven and thirteen tons, moving it, and then putting it all back together.

The greatest care needed to be given during the dismantling stage. Handsaws and steel wires were used because if the cuts were more than 8 millimetres wide they would be visible when the blocks were reassembled. About 500 workers toiled day and night for nine months in order to complete the cutting operations. The larger temple was separated into 807 blocks and the smaller one into 235. The human effort required to save Abu Simbel could scarcely have been less than was needed to build it 3,000 years earlier. Once cut, each block was coated to protect it against splitting and fracturing during transport. After being assigned a number according to a system like those used to classify library books, blocks were carefully loaded onto slow-moving trucks and taken to a temporary holding area.

Engineers knew that when the Aswan dam’s reservoir was completely full it would raise the river’s water level by sixty metres. Based on that knowledge, a relocation site was selected that would be safely above that. The numbered blocks were carefully transported to their new home and reassembled there. However there was one more thing that needed to be done. The complex had originally been carved into a cliff face and a similar appearance had to be recreated at the new location so that it would look like it belonged there. A year was spent building an artificial hill consisting of a domed structure heaped up with boulders and rocks for the complex to rest against. In September 1968, the project was completed and the Abu Simbel temples were safe in their new home. The process of dismantling, relocating, and reassembling them had taken more than four years.

Would Abu Simbel continue to greet the sunrise twice a year?

Not all of the wonders associated with the Abu Simbel temples have to do with their extraordinary workmanship.

Within the main temple in its original location, there was a sanctuary containing four statues standing side by side: that of Ramses II and those of three Egyptian gods, Ra, Amun, and Ptah. Just twice a year, the rays of the rising sun penetrated deep into this chamber and illuminated the statues of Ramses and of two of the gods. This occurred on February 22 and October 22, said to be Ramses’ coronation day and birthday respectively. The sole statue that was not illuminated on these dates was that of Ptah.

So when engineers planned the resiting of Abu Simbel, they also had to be mindful of this 3,000-year-old solar alignment as well. Relocation work was completed on 22 September 1968 and everyone waited anxiously for the morning of October 22, a month later. When the sun rose that day, the faces of Ramses, Ra, and Amun were illuminated but that of Ptah was not. Abu Simbel had been successfully relocated indeed.

Abu Simbel isn’t all that needs rescuing

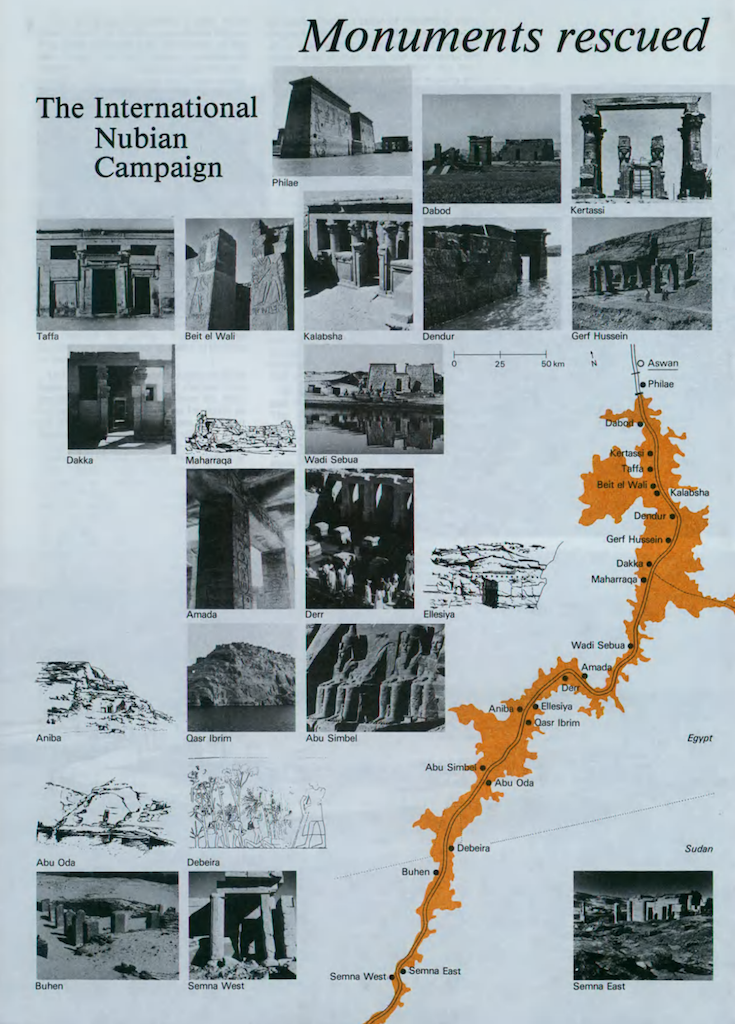

There was far more to the cultural heritage of ancient Nubia than the Abu Simbel temples however. There were dozens of other already identified monuments that needed to be saved as well as a potentially vast trove of treasures waiting to be discovered. When UNESCO called for help in protecting these antiquities in 1960, the first response came from archaeologists. Excavations were carried out and numerous ancient sites, tombs, buildings, and watercourses were unearthed and recorded while thousands of artefacts were also rescued. Twenty-two monuments, the Abu Simbel temple complex being the best-known of them, were also relocated.

One of these monuments was the Roman-era Temple of Kalabsha, a free-standing structure originally built around 30 BCE. Work on rescuing this temple began while the Abu Simbel complex was still being carved up. Because the temple was already being inundated by the Nile for much of the year, its relocation required a different solution. The German engineers working on the project waited until the annual flood peaked, at which time they approached the site with cargo ships, dismantled the topmost layers of building materials above the waterline, and carried them away. As the flood subsided, they returned again and again until the whole structure had been saved. This process took a year and was completed in 1963. The successful salvage and relocation of the Kalabsha temple provided valuable lessons for the engineers working on the Abu Simbel project.

One of the project’s monuments had to be moved intact without dismantling it. This was the Temple of Amada, which couldn’t be cut up into blocks because of the danger of collapse and also because its interior decorations wouldn’t have survived. It was decided to secure the structure with steel bands and mount it on concrete beams that were raised on hydraulic jacks. The whole temple was then moved to its new location above the waterline on rails using a method similar to that of the ancient Egyptians and their wooden rollers: a stretch of track was laid down, the temple was moved along it, and then the rails were collected and laid before the temple again until the final destination was reached.

Saving Philae

With Abu Simbel taken care of, rescuers turned their attentions to the buildings on Philae, an island in the Nile below the Aswan High Dam. During Roman times, there was an Isis sanctuary here that was a place of pilgrimage. In 1972, four years after the successful completion of the Abu Simbel project, work began at Philae. Philae had already been suffering from repeated inundation for decades so the first step involved building a cofferdam around the monuments and pumping the water out from around them so that further work could proceed.

The relocation of some Roman triumphal arches that couldn’t be enclosed in this way required some highly creative thinking given the technology available at the time. Egyptian and British navy divers spent months underwater clearing away mud that had collected around the arches’ bases. Hammers and chisels were then used to dismantle the still-submerged arches’ building-blocks. As each block was extracted, it was raised hydraulically to the surface and cranes were used to take it to its new location. Nearby Agilkia island had been chosen by the Egyptian government as the new site for the temple complex because of its geomorphic resemblance to Philae. As the process of relocation continued, Agilkia was likewise landscaped and planted with palm, henna, acacia, papyrus, and lotus. Twenty-two countries provided financial support towards the 30 million dollars that were spent on saving Philae’s monuments. The seven-year project was completed in 1979.

On 10 March 1980, twenty years after it had begun, UNESCO announced that the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia had been successfully completed. Overall the project had cost more than 80 million dollars, about half of which was paid for by Egypt itself. Egypt was generous in the expression of its gratitude towards the countries that had lent a hand in saving the Nubian cultural heritage. Every nation that had provided financial support received at least a sculpture or other artefact as a gift. The four countries that had been the biggest contributors–United States, Spain, Holland, and Italy–received the rescued Dendur, Debod, Taffa, and Ellesiya temples respectively.

Twenty years, fifty countries, one mission

The international community had much to be excited about at the conclusion of this twenty-year project: countless artefacts had been rescued through the successful completion of a project that had demanded creative engineering skills. Even more important was the huge cooperative effort that was involved: some of the best experts in the world had joined forces and fifty countries had provided technical and financial support. Quite possibly no archaeological site other than Abu Simbel could have more brilliantly demonstrated what countries sharing common values were capable of achieving through cooperation.

Another consequence of the Abu Simbel project’s success was UNESCO’s World Heritage programme. The culture of cooperation that began with Abu Simbel in Egypt continued with other projects such as the protection of Venice and its lagoon in Italy, the excavation of the Mohenjo-daro ruins in Pakistan, and the restoration of the Borobodur temple in Indonesia. The salvage of Abu Simbel was increasingly seen as the inspiration for a concerted effort to protect humanity’s shared world heritage. The idea of safeguarding the world’s places of historical and natural value was first advanced when, at a White House conference in 1965, a proposal was made to set up a “World Heritage Trust” that would “preserve the world's superb natural and scenic areas and historic sites for the present and the future of the entire world citizenry”. Similar proposals were made by the International Union for Conservation of Nature in 1968. In 1972, UNESCO adopted the “Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage”, which led to the creation of the World Heritage list. This convention went into effect in 1975, with the Nubian Monuments in the region from Abu Simbel to Philae being added to the list in 1979.

Around the time that Abu Simbel was being threatened with inundation by Egypt’s Aswan High Dam project, there was a debate over which of two “options” should take precedence: pursuing economic development or preserving cultural heritage. That debate continues to afflict national and international policy even today. The sixty-year-old example of Abu Simbel however shows that it’s possible to do both. What’s more the issue nowadays has been greatly complicated as cultural heritage all over the world comes under increasing pressure from ever-accelerating urbanisation and is threatened by global climate change as well as by deliberate destruction in conflict zones on ideological grounds. Perhaps it’s time to remember the lessons that were learned six decades ago at Abu Simbel. At the very least, those lessons can provide assurance and guidance as we contend with today’s and tomorrow’s problems.

For more detailed information about how Abu Simbel was rescued and relocated, have a look at the videos whose links are given below.

http://www.unesco.org/archives/multimedia/?pg=33&s=films_details&id=876#.VNCj8WiG8Z0

http://www.unesco.org/archives/multimedia/?pg=33&s=films_details&id=1220

http://www.unesco.org/archives/multimedia/?pg=33&s=films_details&id=67

Sources:

- “Victory in Nubia: The Greatest Archaeological Rescue Operation of All Time”, The Unesco Courier, February-March 1980.

http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0007/000747/074755eo.pdf

- “Abu Simbel: Now or never”, The Unesco Courier, October 1961.

http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0006/000642/064240eo.pdf

- Zahi Hawass, Mysteries of Abu Simbel, University of Cairo Press, 2000

- “Egypt’s Exquisite Temples That Had To be Moved”, Laura Kiniry, BBC Travel, 10 April 2018

http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20180409-egypts-exquisite-temples-that-had-to-be-moved

- “Monuments of Nubia-International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia”, UNESCO

https://whc.unesco.org/en/activities/172/

- “Monster Moves: Rescuing Ramesses”, National Geographic, 4 March 2008