Just about anywhere you may go in Turkey you’re sure to come across local legends about fabulous treasures that are to be found in the vicinity. Handed down from generation to generation, stories about these mysterious troves and their associated maps and clues are the elements of popular culture and provoke both curiosity and speculation.

Although treasure-related narratives may provide entertaining plots for thriller-mysteries, dynastic melodramas, and action-hero movies, the fact is that real-world treasure-hunting poses serious problems for those involved in the preservation of cultural and historical heritage. And with archaeological remains, ancient mounds and cities, and historical structures all over Turkey continuing to be endangered by illegal excavations.

What is a treasure? And what isn’t?

The current regulation governing treasure-hunting, as defined in the Cultural and Natural Heritage Protection Act (Statute 2863), was published in 1984.[1] This regulation sets out the conditions under which individuals may legally engage in treasure-hunting in Turkey. Under the regulation, anyone who is qualified may obtain a “treasure-hunting license” that allows them to search for treasure, but only at a specific location and only for a limited time.

Those for whom treasure-hunting is a hobby or perhaps even a form of exercise, the biggest question that needs to be answered is “What is a treasure?”. The Turkish civil code defines the word in very general terms as “any valuable thing that was buried or hidden long before it was found and, according to circumstances, whose owner can no longer be ascertained definitively.”[2]

Based on that general definition, it might seem that buried things that have historical or scientific importance should also qualify as “treasure”; however the Treasure-Hunting Regulation also says that treasure-hunting licenses can only be issued to search in places that don’t qualify as “cultural or natural heritage that must be protected” as defined in Statute 2863.[3]

At this point then it’s worthwhile taking a look at what that law says constitutes “cultural and natural heritage”. According to article 6 of the act, it consists of:

- a) Natural properties that need to be protected and immovable properties built before the end of the 19th century;

- b) Immovable properties built after that date but whose protection the Ministry of Culture and Tourism deems to be necessary based on their importance or attributes;

- c) Immovable cultural properties located within protected areas;

- d) Domiciles which were settings for historical events associated with the War of Independence or the establishment of the Republic of Turkey or which were used by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

In other words, licenses can’t be issued to hunt for treasure in any of these places.

An even longer list

Getting into the nitty-gritty details of places that Statute 2863 does not allow treasure-hunting licenses to be issued for, we come up with an even longer and more formidable list of “examples” of immovable cultural properties:

“Rock tombs; cliff surfaces with inscriptions, pictures, or reliefs on them; caves with pictures in them; mounds, tumuli, archaeological sites, acropolises, necropolises; citadels, fortresses, bastions, fortifications; historically important military barracks, batteries, and strongholds as well as weapons of war installed in them; ruins; caravanserais, inns, baths, madrassas; tombs, mausoleums, epitaphs; bridges, aqueducts, waterworks, cisterns, wells; the remains of historically important roads, milestones, ancient boundary markers, steles, altars; shipyards, docks; historically important palaces, kiosks, houses, waterfront mansions, great houses; mosques, masjids, coffin rests, prayer platforms; large and small public fountains; almshouses; mints; infirmaries; clock houses; gold or silver wire workshops; dervish lodges and hermitages; cemeteries and graveyards; arcades, marketplaces, covered bazaars; sarcophaguses, headstones; synagogues, basilicas, churches, monasteries, kulliyes; remains of ancient monuments or walls; frescoes, reliefs, mosaics; fairy chimneys; similar immovable properties.”

Where and how to hunt for treasure

License-holders are allowed to search for treasure in places other than these but only under the conditions prescribed by law. For one thing, the place where the hunting is permitted has to be exactly defined; for another, the place can’t be more than 100 square meters in area. You can’t search for treasure on someone else’s behalf and if you hold one of these licenses, you can’t transfer it to someone else.

All searches must be carried out under the supervision of tax or customs officers who’ve been assigned to the task by the nearest museum and the license-holder is responsible for paying the per diem allowances of these officials. Licenses are valid for no more than a month and if nothing is found during that time, any digging that is in progress must be wound up.

What every treasure-hunter dreams of

If anything in the nature of a cultural property is turned up during excavation, the digging must stop immediately and the license-holder has no claim whatsoever to it. This is because in order for something to qualify as a “treasure”, it must not have any historical or scientific value, it must not be in need of protection, and it must have been buried at some time in the past and its owner can no longer be identified.

Probably what every treasure-hunter dreams of is chancing upon a hoard of glistening gold though it’s certainly true that there are some for whom the possibility of coming across old coins (so-called “coin shooting”) can be an important source of motivation.

There are also those who maintain that licensed private treasure-hunting can even be beneficial because it leads to supervised digging and to the unearthing of cultural properties in places that might otherwise be ignored by authorities. The truth of the matter however is that licensed treasure-hunters’ finds could result in the destruction of cultural heritage because they provoke illegal excavation by others.

Is licensed treasure-hunting really worth all the time and effort?

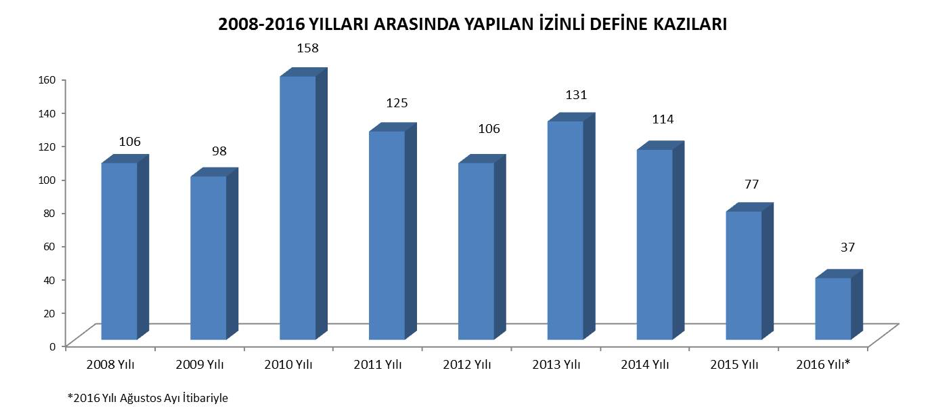

The accompanying chart shows the numbers of excavations that were carried out by licensed treasure-hunters in Turkey between 2008 and 2016. In the “Frequently-Asked-Questions” section about treasure-hunting on the ministry’s website, the answer to the question “Have licensed treasure-hunters found any treasure?” is “No finds whatsoever have been encountered in the course of licensed treasure-hunting excavations.”

So why does licensed treasure-hunting exist at all?

Why then does the state allow licensed treasure-hunting and why is there a legal framework governing it?

The short answer is that people everywhere are fascinated by treasure and treasure-hunting. It’s a fascination that’s nourished in many different ways and is easy to provoke. It’s a human urge whose roots run deep and exploring them properly would require a separate study of its own. That being so, licensing can be seen as an attempt to bring this urge under control by allowing people to indulge in it under strictly regulated conditions.

Self-styled “expert treasure-hunter and clues analyst” Uğur Kulaç provoked a storm of criticism after promoting metal detectors on a TV program.

The problem is that licensed treasure-hunting is one of the things that is encouraging the use of metal detectors. Neither the sale nor the use of metal detectors is currently subject to systematic regulation in Turkey.

The use of metal detectors is prohibited in places that the law recognizes as containing cultural heritage that’s in need of protection: since excavation isn’t allowed in such places, preliminary exploration of any kind isn’t allowed either; however nothing prevents metal detectors from being used outside such areas. Unfortunately it’s unlicensed treasure-hunters who cause the greatest harm to archaeological sites and there’s nothing to prevent them from using metal detectors wherever they like.

Sources:

[1] http://teftis.kulturturizm.gov.tr/TR,14428/define-arama-yonetmeligi.html

[2] http://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/MevzuatMetin/1.5.4721.pdf

[3] http://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/Metin.Aspx?MevzuatKod=1.5.2863&MevzuatIliski=0&sourceXmlSearch=